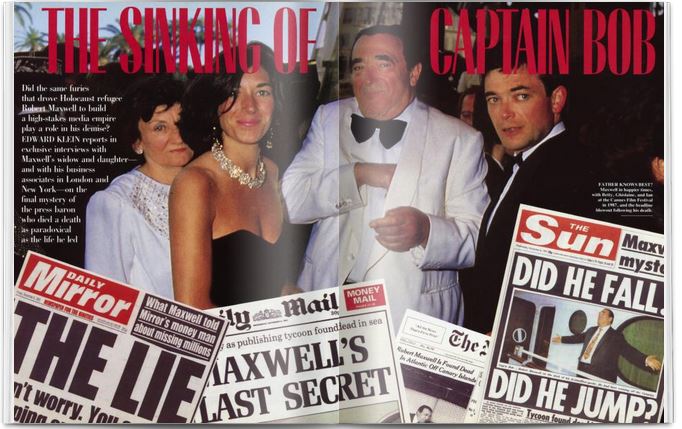

THE SINKING OF CAPTAIN BOB

Did the same furies that drove Holocaust refugee Robert Maxwell to build a high-stakes media empire play a role in his demise? EDWARD KLEIN reports in exclusive interviews with Maxwell’s widow and daughter—and with his business associates in London and New York—on the final mystery of the press baron who died a death as paradoxical as the life he led

am utterly confused,” said Elisabeth Meynard Maxwell, the elegant French-born widow of Robert Maxwell. ”The worst part for me—the most difficult part—is that when I read this deluge about my husband I think I’m reading about a man I never knew. I am trying to adjust to a pattern of behavior that is not at all convergent with the man I knew, and that doesn’t ring true for all the things Bob represented in my life. I am trying to decipher from this torrent of words the things that may be true from those I know are total lies.”

She was sitting on the edge of a chintz-covered love seat, sipping tea and staring at me over the rim of her cup with her cool teal-blue eyes. We were talking about how the whole of British society seemed to be gloating over the fall of the house of Maxwell. Some newspapers reported that Betty Maxwell had closed her Oxford mansion—with its soaring stained-glass window depicting Maxwell as Samson at the gates of Gaza—and absconded to her thatch-roofed chateau near Bergerac, in southwest France. But in fact the iron-willed matriarch of the Maxwell family was still living in her adopted land, shuttling from lawyer to lawyer in an effort to unravel the tangled skein of her husband’s financial affairs and to salvage whatever she could of her own inheritance.

She met frequently with her embattled sons, Ian and Kevin, both of whom were widely suspected of having aided their father in his illegal depredations. She delivered pep talks to the family—her seven surviving children and their spouses—reassuring them all that, despite the scandalous collapse of the Maxwell empire, life with Father had not been a total sham. She spoke daily to her youngest daughter, Ghislaine, who lives in New York and who was already discreetly inquiring of friends whether they would be willing to help provide surety for bail in the event her brothers were arrested. ”Ghislaine is the baby of the family and the one who was closest to her father,” her mother told me. ”The whole of Ghislaine’s world has collapsed, and it will be very difficult for her to continue.”

Our interview was arranged by a mutual acquaintance, Samuel Pisar, a well-known international lawyer and a survivor of Auschwitz, who in 1988 had been invited along with Elie Wiesel and Simone Veil to address a conference on the Holocaust organized by Betty at Oxford. Through Betty, Pisar had become Maxwell’s Paris-based avocat. Since Maxwell’s sons were not Jewish, it was Pisar who had been asked by the Israelis and Betty to say Kaddish at Maxwell’s extraordinary quasi-state funeral in Jerusalem, where, five days after his death at sea last November, the tycoon was buried according to the Orthodox custom of Israel, wrapped in a simple white shroud and without a coffin.

“They say I have £500,000,” said Betty Maxwell. “Those are lies. I haven’t anything.”

It had been agreed that our meeting should be kept secret, so I had rented a sitting room in the Dorchester hotel, across from Hyde Park in central London, without revealing to the manager the identity of my guest. She arrived dressed in couture widow’s weeds, a trim, stylish woman who hardly showed her seventy years.

“You are looking quite well,” I said after she had freshened her makeup in the powder room. We had met once before, at a testimonial dinner for her deceased husband in New York.

”Actually,” she responded with a Gallic shrug, ”I feel quite tired. I am normally an extremely good sleeper, but recently I’ve had to live by night and sleep by day to avoid the reptiles.”

There was no mistaking her reference to the slithering frenzy of the British press, especially its venomous tabloids, one of which—the Daily Mirror—had been owned by her husband. Reporters were having a field day with the revelations that Maxwell, an avowed socialist, had plundered the Mirror’s pension fund, pillaged the treasuries of two of his public companies, shifted vast sums in and out of secret family trusts in Liechtenstein, illegally propped up the share price of Maxwell Communications Corporation, racked up debts of more than $5 billion, and—perhaps most unforgivable of all—ensnared Ian and Kevin in his malfeasance and left them exposed to criminal prosecution.

A little more than a month had passed since Maxwell tumbled off his yacht and died under mysterious circumstances, and Betty Maxwell was numb from the savage public battering. People were calling her husband ”rogue,” “crook,” “bully,” “thief,” “megalomaniac,” “gangster.” They told lurid tales of his sex orgies with midget Filipino hookers. Former employees, who had supped at his table, described how the 310-pound media mogul gorged on soupspoonful after soupspoonful of caviar. They painted a portrait of an erratic and cruel tyrant, one who used Turkish towels for toilet paper. Members of the British establishment—shamed and chagrined that they had lent him respectability along with money—behaved as though they had hardly known the man. Journalists wrote that he was a spy for the K.G.B. or Mossad or Czech intelligence—or all three. Others charged that Maxwell’s emergence late in life as a born-again Jew was nothing but a charade to further his business interests in Israel and New York City.

This had gone on for weeks, and depending on which day’s newspapers Betty Maxwell picked up, or whom her sons talked to, there was yet another theory about how her husband had met his end. One claimed that Maxwell had died of a heart attack while having sex with a mistress on the six-foot-wide bed in the main cabin of his yacht as it sailed off the Canary Islands (this, naturally, was dubbed the Nelson Rockefeller theory). Another had him being assassinated on the high seas by frogmen (a theory retailed by a number of tabloids), or brutally beaten by unknown assailants, then tossed into the ocean. A third said he had committed suicide to avoid facing exposure and public humiliation (subscribed to by a large chorus of those I interviewed in England). A fourth argued that he had accidentally fallen off the slippery deck of his boat in the early morning hours and drowned (as his crew and family believed). A fifth, which appeared in The Guardian, was the wildest theory of them all; the normally sober newspaper, freed at last from the threat of the libel writs that Maxwell had used throughout his life to effectively silence his critics, speculated that the body identified by Elisabeth Maxwell was not that of her husband at all, but a corpulent substitute, and that Maxwell had done a world-class bunk.

More than once during our conversation, Betty Maxwell wondered where in this dark and twisted portrait of her husband she could find the familiar shape of the man she had known. Where, for instance, was the man who had—in her words—”cried his eyes out” at the bedside of their eldest son, Michael, who was critically injured in a car accident when he was fifteen and lay in a coma for six years before he died? Where was the man who had “revolutionized scientific publishing” with Pergamon Press? Where was the man who had performed all those acts of “unsung generosity”? Maxwell had helped fly children from the Chernobyl area to Israel, where they could receive proper medical treatment. And where was the man who just last March, on the eve of his triumphant acquisition of the New York Daily News, had thrown a lavish seventieth-birthday party for his wife in this very hotel, an event attended by bankers and tycoons, lords and peers, ambassadors and celebrities—the cream of British society—who were now denouncing him as a fraud?

No wonder Betty Maxwell was confused. She had lovingly preserved more than forty scrapbooks, bound each year in hand-tooled leather, of every article about and photograph of her husband that had ever been published since their marriage forty-six years ago. The clippings from one of those years alone weighed in at sixty pounds. Now, suddenly, she was forced to confront the awful realization that she had never known the full truth about the man she loved.

But then, after all, who had?

Almost thirty years ago, The Sunday Times of London made the first serious attempt to unravel the mystery of Robert Maxwell, a man born in abject poverty in the Carpathian Mountains of Czechoslovakia and originally named Jan Ludvik Hoch. A subsequent Sunday Times exposé of Maxwell was conducted amid what became a typical Maxwell counterbarrage—five libel actions, a demand by him to the publisher that the editor be fired, and the reporting of the editor for punishment to the House of Commons Committee of Privileges for printing that Maxwell had fiddled the figures when he was chairman of the committee that ran the members’ restaurant.

Shortly after the newspaper began its reporting, in the early 1960s, Maxwell became a Labour member of Parliament, but his chameleonlike penchant for changing names— his own as well as those of his proliferating companies—was barely known. Nor were very many people aware of Maxwell’s obsession with appearances and titles. Long after he had been decorated with the Military Cross for bravery in World War II, Maxwell flouted British tradition by insisting that his name appear preceded by “Captain”—his rank when he was demobilized from the British Army—and followed by the imposing initials “M.C.”

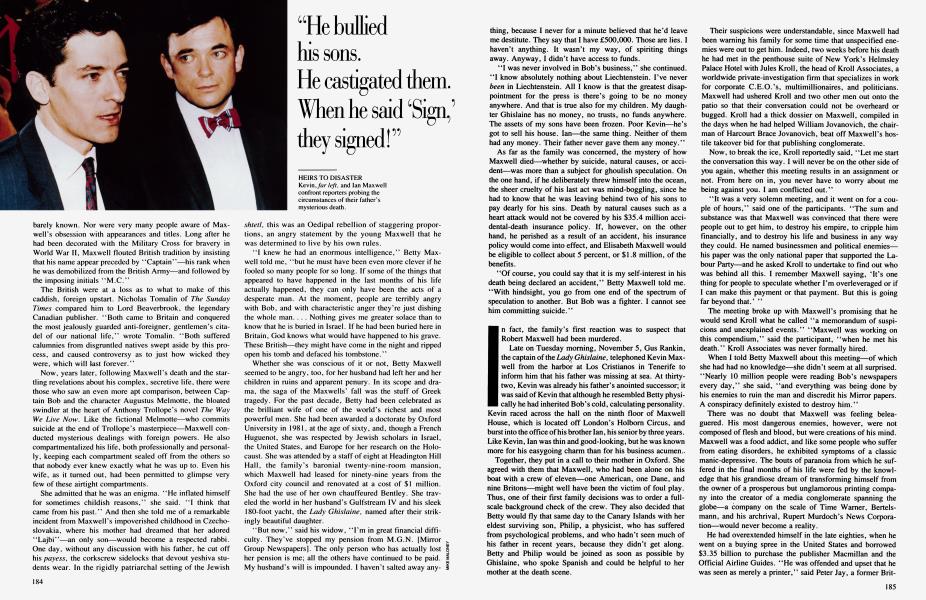

“He bullied his sons. He castigated them. When he said ‘Sign,’ they signed!”

The British were at a loss as to what to make of this caddish, foreign upstart. Nicholas Tomalin of The Sunday Times compared him to Lord Beaverbrook, the legendary Canadian publisher. “Both came to Britain and conquered the most jealously guarded anti-foreigner, gentlemen’s citadel of our national life,” wrote Tomalin. “Both suffered calumnies from disgruntled natives swept aside by this process, and caused controversy as to just how wicked they were, which will last forever.”

Now, years later, following Maxwell’s death and the startling revelations about his complex, secretive life, there were those who saw an even more apt comparison, between Captain Bob and the character Augustus Melmotte, the bloated swindler at the heart of Anthony Trollope’s novel The Way We Live Now. Like the fictional Melmotte—who commits suicide at the end of Trollope’s masterpiece—Maxwell conducted mysterious dealings with foreign powers. He also compartmentalized his life, both professionally and personally, keeping each compartment sealed off from the others so that nobody ever knew exactly what he was up to. Even his wife, as it turned out, had been permitted to glimpse very few of these airtight compartments.

She admitted that he was an enigma. “He inflated himself for sometimes childish reasons,” she said. “I think that came from his past.” And then she told me of a remarkable incident from Maxwell’s impoverished childhood in Czechoslovakia, where his mother had dreamed that her adored “Lajbi”—an only son—would become a respected rabbi. One day, without any discussion with his father, he cut off his payess, the corkscrew sidelocks that devout yeshiva students wear. In the rigidly patriarchal setting of the Jewish shtetl, this was an Oedipal rebellion of staggering proportions, an angry statement by the young Maxwell that he was determined to live by his own rules.

“I knew he had an enormous intelligence,” Betty Maxwell told me, “but he must have been even more clever if he fooled so many people for so long. If some of the things that appeared to have happened in the last months of his life actually happened, they can only have been the acts of a desperate man. At the moment, people are terribly angry with Bob, and with characteristic anger they’re just dishing the whole man. . . . Nothing gives me greater solace than to know that he is buried in Israel. If he had been buried here in Britain, God knows what would have happened to his grave. These British—they might have come in the night and ripped open his tomb and defaced his tombstone.”

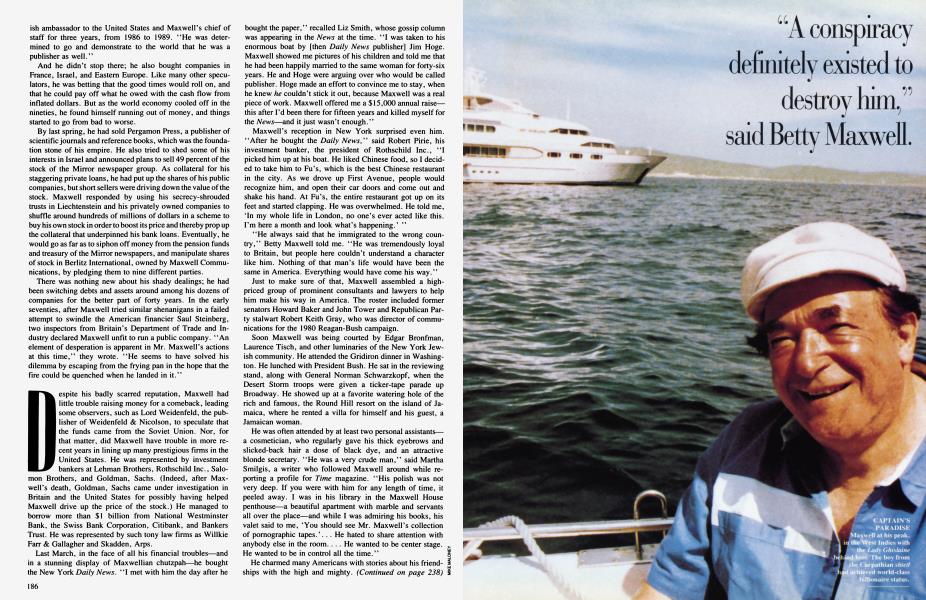

Whether she was conscious of it or not, Betty Maxwell seemed to be angry, too, for her husband had left her and her children in ruins and apparent penury. In its scope and drama, the saga of the Maxwells’ fall was the stuff of Greek tragedy. For the past decade, Betty had been celebrated as the brilliant wife of one of the world’s richest and most powerful men. She had been awarded a doctorate by Oxford University in 1981, at the age of sixty, and, though a French Huguenot, she was respected by Jewish scholars in Israel, the United States, and Europe for her research on the Holocaust. She was attended by a staff of eight at Headington Hill Hall, the family’s baronial twenty-nine-room mansion, which Maxwell had leased for ninety-nine years from the Oxford city council and renovated at a cost of $1 million. She had the use of her own chauffeured Bentley. She traveled the world in her husband’s Gulfstream IV and his sleek 180-foot yacht, the Lady Ghislaine, named after their strikingly beautiful daughter.

“But now,” said his widow, “I’m in great financial difficulty. They’ve stopped my pension from M.G.N. [Mirror Group Newspapers]. The only person who has actually lost her pension is me; all the others have continued to be paid. My husband’s will is impounded. I haven’t salted away anything, because I never for a minute believed that he’d leave me destitute. They say that I have £500,000. Those are lies. I haven’t anything. It wasn’t my way, of spiriting things away. Anyway, I didn’t have access to funds.

“I was never involved in Bob’s business,” she continued. ”I know absolutely nothing about Liechtenstein. I’ve never been in Liechtenstein. All I know is that the greatest disappointment for the press is there’s going to be no money anywhere. And that is true also for my children. My daughter Ghislaine has no money, no trusts, no funds anywhere. The assets of my sons have been frozen. Poor Kevin—he’s got to sell his house. Ian—the same thing. Neither of them had any money. Their father never gave them any money.”

As far as the family was concerned, the mystery of how Maxwell died—whether by suicide, natural causes, or accident—was more than a subject for ghoulish speculation. On the one hand, if he deliberately threw himself into the ocean, the sheer cruelty of his last act was mind-boggling, since he had to know that he was leaving behind two of his sons to pay dearly for his sins. Death by natural causes such as a heart attack would not be covered by his $35.4 million accidental-death insurance policy. If, however, on the other hand, he perished as a result of an accident, his insurance policy would come into effect, and Elisabeth Maxwell would be eligible to collect about 5 percent, or $1.8 million, of the benefits.

”Of course, you could say that it is my self-interest in his death being declared an accident,” Betty Maxwell told me. “With hindsight, you go from one end of the spectrum of speculation to another. But Bob was a fighter. I cannot see him committing suicide.”

In fact, the family’s first reaction was to suspect that Robert Maxwell had been murdered.

Late on Tuesday morning, November 5, Gus Rankin, the captain of the Lady Ghislaine, telephoned Kevin Maxwell from the harbor at Los Cristianos in Tenerife to inform him that his father was missing at sea. At thirty-two, Kevin was already his father’s anointed successor; it was said of Kevin that although he resembled Betty physically he had inherited Bob’s cold, calculating personality. Kevin raced across the hall on the ninth floor of Maxwell House, which is located off London’s Holborn Circus, and burst into the office of his brother Ian, his senior by three years. Like Kevin, Ian was thin and good-looking, but he was known more for his easygoing charm than for his business acumen..

Together, they put in a call to their mother in Oxford. She agreed with them that Maxwell, who had been alone on his boat with a crew of eleven—one American, one Dane, and nine Britons—might well have been the victim of foul play. Thus, one of their first family decisions was to order a full-scale background check of the crew. They also decided that Betty would fly that same day to the Canary Islands with her eldest surviving son, Philip, a physicist, who has suffered from psychological problems, and who hadn’t seen much of his father in recent years, because they didn’t get along. Betty and Philip would be joined as soon as possible by Ghislaine, who spoke Spanish and could be helpful to her mother at the death scene.

Their suspicions were understandable, since Maxwell had been warning his family for some time that unspecified enemies were out to get him. Indeed, two weeks before his death he had met in the penthouse suite of New York’s Helmsley Palace Hotel with Jules Kroll, the head of Kroll Associates, a worldwide private-investigation firm that specializes in work for corporate C.E.O.’s, multimillionaires, and politicians. Maxwell had ushered Kroll and two other men out onto the patio so that their conversation could not be overheard or bugged. Kroll had a thick dossier on Maxwell, compiled in the days when he had helped William Jovanovich, the chairman of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, beat off Maxwell’s hostile takeover bid for that publishing conglomerate.

Now, to break the ice, Kroll reportedly said, “Let me start the conversation this way. I will never be on the other side of you again, whether this meeting results in an assignment or not. From here on in, you never have to worry about me being against you. I am conflicted out.”

“It was a very solemn meeting, and it went on for a couple of hours,” said one of the participants. “The sum and substance was that Maxwell was convinced that there were people out to get him, to destroy his empire, to cripple him financially, and to destroy his life and business in any way they could. He named businessmen and political enemies— his paper was the only national paper that supported the Labour Party—and he asked Kroll to undertake to find out who was behind all this. I remember Maxwell saying, ‘It’s one thing for people to speculate whether I’m overleveraged or if I can make this payment or that payment. But this is going far beyond that.’ ”

The meeting broke up with Maxwell’s promising that he would send Kroll what he called “a memorandum of suspicions and unexplained events.” “Maxwell was working on this compendium,” said the participant, “when he met his death.” Kroll Associates was never formally hired.

When I told Betty Maxwell about this meeting—of which she had had no knowledge—she didn’t seem at all surprised. “Nearly 10 million people were reading Bob’s newspapers every day,” she said, “and everything was being done by his enemies to ruin the man and discredit his Mirror papers. A conspiracy definitely existed to destroy him.”

There was no doubt that Maxwell was feeling beleaguered. His most dangerous enemies, however, were not composed of flesh and blood, but were creations of his mind. Maxwell was a food addict, and like some people who suffer from eating disorders, he exhibited symptoms of a classic manic-depressive. The bouts of paranoia from which he suffered in the final months of his life were fed by the knowledge that his grandiose dream of transforming himself from the owner of a prosperous but unglamorous printing company into the creator of a media conglomerate spanning the globe—a company on the scale of Time Warner, Bertelsmann, and his archrival, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation—would never become a reality.

He had overextended himself in the late eighties, when he went on a buying spree in the United States and borrowed $3.35 billion to purchase the publisher Macmillan and the Official Airline Guides. “He was offended and upset that he was seen as merely a printer,” said Peter Jay, a former British ambassador to the United States and Maxwell’s chief of staff for three years, from 1986 to 1989. “He was determined to go and demonstrate to the world that he was a publisher as well.”

And he didn’t stop there; he also bought companies in France, Israel, and Eastern Europe. Like many other speculators, he was betting that the good times would roll on, and that he could pay off what he owed with the cash flow from inflated dollars. But as the world economy cooled off in the nineties, he found himself running out of money, and things started to go from bad to worse.

By last spring, he had sold Pergamon Press, a publisher of scientific journals and reference books, which was the foundation stone of his empire. He also tried to shed some of his interests in Israel and announced plans to sell 49 percent of the stock of the Mirror newspaper group. As collateral for his staggering private loans, he had put up the shares of his public companies, but short sellers were driving down the value of the stock. Maxwell responded by using his secrecy-shrouded trusts in Liechtenstein and his privately owned companies to shuffle around hundreds of millions of dollars in a scheme to buy his own stock in order to boost its price and thereby prop up the collateral that underpinned his bank loans. Eventually, he would go as far as to siphon off money from the pension funds and treasury of the Mirror newspapers, and manipulate shares of stock in Berlitz International, owned by Maxwell Communications, by pledging them to nine different parties.

There was nothing new about his shady dealings; he had been switching debts and assets around among his dozens of companies for the better part of forty years. In the early seventies, after Maxwell tried similar shenanigans in a failed attempt to swindle the American financier Saul Steinberg, two inspectors from Britain’s Department of Trade and Industry declared Maxwell unfit to run a public company. “An element of desperation is apparent in Mr. Maxwell’s actions at this time,” they wrote. “He seems to have solved his dilemma by escaping from the frying pan in the hope that the fire could be quenched when he landed in it.”

Despite his badly scarred reputation, Maxwell had little trouble raising money for a comeback, leading some observers, such as Lord Weidenfeld, the publisher of Weidenfeld & Nicolson, to speculate that func*s came from the Soviet Union. Nor, for that matter, did Maxwell have trouble in more recent years in lining up many prestigious firms in the United States. He was represented by investment bankers at Lehman Brothers, Rothschild Inc., Salomon Brothers, and Goldman, Sachs. (Indeed, after Maxwell’s death, Goldman, Sachs came under investigation in Britain and the United States for possibly having helped Maxwell drive up the price of the stock.) He managed to borrow more than $1 billion from National Westminster Bank, the Swiss Bank Corporation, Citibank, and Bankers Trust. He was represented by such tony law firms as Willkie Farr & Gallagher and Skadden, Arps.

Last March, in the face of all his financial troubles—and in a stunning display of Maxwellian chutzpah—he bought the New York Daily News. “I met with him the day after he bought the paper,” recalled Liz Smith, whose gossip column was appearing in the News at the time. “I was taken to his enormous boat by [then Daily News publisher] Jim Hoge. Maxwell showed me pictures of his children and told me that he had been happily married to the same woman for forty-six years. He and Hoge were arguing over who would be called publisher. Hoge made an effort to convince me to stay, when he knew he couldn’t stick it out, because Maxwell was a real piece of work. Maxwell offered me a $15,000 annual raise— this after I’d been there for fifteen years and killed myself for the News—and it just wasn’t enough.”

Maxwell’s reception in New York surprised even him. “After he bought the Daily News,” said Robert Pirie, his investment banker, the president of Rothschild Inc., “I picked him up at his boat. He liked Chinese food, so I decided to take him to Fu’s, which is the best Chinese restaurant in the city. As we drove up First Avenue, people would recognize him, and open their car doors and come out and shake his hand. At Fu’s, the entire restaurant got up on its feet and started clapping. He was overwhelmed. He told me, ‘In my whole life in London, no one’s ever acted like this. I’m here a month and look what’s happening.’ ”

“He always said that he immigrated to the wrong country,” Betty Maxwell told me. “He was tremendously loyal to Britain, but people here couldn’t understand a character like him. Nothing of that man’s life would have been the same in America. Everything would have come his way.”

Just to make sure of that, Maxwell assembled a high-priced group of prominent consultants and lawyers to help him make his way in America. The roster included former senators Howard Baker and John Tower and Republican Party stalwart Robert Keith Gray, who was director of communications for the 1980 Reagan-Bush campaign.

Soon Maxwell was being courted by Edgar Bronfman, Laurence Tisch, and other luminaries of the New York Jewish community. He attended the Gridiron dinner in Washington. He lunched with President Bush. He sat in the reviewing stand, along with General Norman Schwarzkopf, when the Desert Storm troops were given a ticker-tape parade up Broadway. He showed up at a favorite watering hole of the rich and famous, the Round Hill resort on the island of Jamaica, where he rented a villa for himself and his guest, a Jamaican woman.

He was often attended by at least two personal assistants— a cosmetician, who regularly gave his thick eyebrows and slicked-back hair a dose of black dye, and an attractive blonde secretary. “He was a very crude man,” said Martha Smilgis, a writer who followed Maxwell around while reporting a profile for Time magazine. “His polish was not very deep. If you were with him for any length of time, it peeled away. I was in his library in the Maxwell House penthouse—a beautiful apartment with marble and servants all over the place—and while I was admiring his books, his valet said to me, ‘You should see Mr. Maxwell’s collection of pornographic tapes.’… He hated to share attention with anybody else in the room…. He wanted to be center stage. He wanted to be in control all the time.”

He charmed many Americans with stories about his friendships with the high and mighty. “He was obviously a guy whose persona was totally overtaken by his public image, by what he purported to be, which was a world-class billionaire tycoon,” said one of his lawyers. “He was celebrity-mad. He’d cut short a business conference just to show you a picture of him shaking hands with Gorbachev.”

“A conspiracy definitely existed to destroy him,” said Betty Maxwell.

Americans were impressed by his size, his plummy upper-class British accent, and his natural storyteller’s wit. “He once told me a story about his meeting with Brezhnev,” said John Campi, vice president of promotion for the Daily News. “Brezhnev asked him what would have happened if Khrushchev had been assassinated instead of Kennedy. And Maxwell replied, ‘Well, one thing is for sure. Mr. Onassis would not have married Mrs. Khrushchev.’ ”

But while things appeared to be going swimmingly in America in the summer of 1991, they were fast falling apart in Britain. The Financial Times raised serious questions about the mysterious rise in the price of Maxwell Communications stock. The British Broadcasting Company’s Panorama news program and The Independent newspaper launched separate investigations of Maxwell’s finances. A lawyer for the pensioners of the Mirror Group began expressing concern about possible manipulations of the fund. Peter Walker, a former Tory Cabinet minister and well-connected business executive, announced that, after considering an offer to assume the chairmanship of Maxwell Communications, he had thought better of it. And Maxwell himself, having bet and lost millions in the foreign-exchange market, had to mortgage the Mirror newspaper buildings for $166 million.

“I had stayed on relatively good terms with him, despite my leaving his employ,” said Peter Jay, his former chief of staff, “and one day he telephoned me about what he called his cold. This was in May or June. You know, he had had a lung removed in the mid-fifties, and he often suffered from pulmonary edema. I told him to take Benylin. It’s a schoolboy cough mixture, an expectorant. He said thank you, and the word ‘friend’ came up. And suddenly he said, ‘You’re the only friend I have.’ And I said, ‘Bob, don’t be ridiculous.’ Old-fashioned English schoolboy that I am, if you take someone’s check, it is not civilized or respectable, the moment you’re out the door, to bad-mouth the guy. I didn’t. And I suppose that explains why he called me his only friend. I was in no sense his friend.”

Nor did another old-fashioned English schoolboy, Lord Donoughue, consider himself a friend, even when he worked for Maxwell as vice-chairman of London & Bishopsgate International Investment Management. According to Bernard Donoughue, who was a Labour peer, he began to complain vociferously about Maxwell’s habit of lending out pension-fund stocks.

“His moods swung violently from beaming, relaxed confidence to surly, snarling aggression,” Lord Donoughue told me. “In July, during a meeting in his study at Maxwell House, he accused me of betraying him, because I sided with those who complained about his stock lending. I said, ‘The stock lending must stop.’ He said, ‘It’s none of your fucking business. I’m chairman and I’m responsible.’ I said, ‘I have an obligation, too.’ We also had a row about our trying to tell the pension-fund trustees what he was doing. And he said, again, ‘It’s none of your fucking business to tell the trustees. I’m the chairman of the trustees.’

“Most of our dealings were with Kevin, with whom my relations were usually courteous but grew increasingly distant,” Lord Donoughue continued. “I saw Kevin on July 31, at a company meeting in Edinburgh, my last day with London & Bishopsgate. I had been scheduled to leave the previous December, and I was fed up with the whole bloody thing, because I didn’t know what was going on. I didn’t know what I didn’t know. And Kevin and I had had words. Kevin normally never lost his temper. He had a kind of almost clinical control. Kevin could be mean, like his father. I was complaining about the stock-lending scheme, and about the people who were in charge.

“It was a gamble working for Maxwell,” he went on. “I went to work for him because I was bored in the City, and although I believed he was a rogue and a pirate, I did not believe he was a crook. Now everybody is functioning on twenty-twenty hindsight, and they know what a crook he was. But the reality was that until about July or August people still found him fascinating.”

It was at that time, in late summer, that Maxwell appeared frequently at London’s casinos, playing three tables at once, dropping $2.5 million in a single night. For years he had been an inveterate gambler, but this was the behavior of a desperate man. He knew that time was running out. The Wall Street Journal was preparing a piece on his crumbling empire. Seymour Hersh, the American reporter, was bringing out a book on Israel’s secret nuclear arsenal called The Samson Option, in which it was alleged that Maxwell had close ties to the Israeli intelligence service, Mossad.

“At the end of his life, Bob was no longer able to tackle very complicated problems with the same sharpness that he had displayed throughout his entire life,” Betty Maxwell told me. “I think he was extremely tired, not only because of his business but because of all these attacks to which he was subjected. In England, they don’t tolerate success.”

Not everyone bought that explanation. “Betty is clearly going to live out a fantasy for the rest of her life that Robert was a good man, and they were all jealous of him for making so much money,” said Roy Greenslade, a former editor of the Daily Mirror, whose tentatively titled Maxwell’s Fall: An Insider’s Account is scheduled for publication late this spring. “He fooled the world. Usually you can’t fool those close to you. But Betty knew nothing about anything bad he did. They had lived separately for a long time.”

“Maxwell never wanted Betty near him except when it was judicious to have her attend a dinner or send her to take his place at a charity function,” said another former top executive at the Mirror. “Even when they shared the same hotel, she was put on a different floor.”

However, many people found it implausible that a woman of Betty Maxwell’s obvious intellect had remained in total ignorance of her husband’s activities for nearly half a century. One businessman, for instance, recalled negotiating with Maxwell in his wife’s presence; Bob, he said, would turn to Betty whenever the questions got knotty, and consult with her in French. “She may not have known all the details,” said this businessman, “but I cannot believe that she did not have some idea of what he was up to.”

In Maxwell’s final days, his sons may have known that Götterdämmerung was lurking around the comer. By then, Maxwell was ordering huge transfers from the Mirror pension funds: the final tally was three-quarters of a billion dollars. Two weeks before his father’s death, as money began to dry up, Ian Maxwell reportedly telephoned an acquaintance in Argentina and said, “It’s every man for himself.”

“Maxwell was increasingly paranoid,” Ernest Burrington, the Mirror Group’s deputy chairman, told me. To prove his point, Burrington gave me a tour of the executive suite, showing me where Maxwell had bugged the offices of his own executives. The police had recently ripped out wall panels, uncovering the secret bugging equipment. “He was a naturally secretive man who was concerned about people telling tales about him,” Burrington said. “I remember how concerned and jumpy the Maxwells were after the last board meeting. I was phoned by Ian Maxwell, who said, ‘What is your finance man up to now? I’m told that after the board meeting he handed an envelope to one of the nonexecutive board directors. Don’t you know that that envelope could include figures?’ ”

Before the boss left for his fateful cruise on his yacht, Burrington said he demanded an explanation from Maxwell for the mysterious disappearance of $83 million in Mirror funds, and Maxwell promised that he would discuss the matter with him when he returned. Maxwell also knew that Coopers & Lybrand Deloitte was scheduled to do its next audit of the pension fund in a couple of months, when it would surely discover the missing funds. One of his banks, the Swiss Bank Corporation, was threatening to go to the Serious Fraud Office and blow the whistle unless Maxwell delivered stock—stock he didn’t legally control, because he had already sold it or pledged it as collateral to other creditors. What’s more, Maxwell was informed by Kevin that Goldman, Sachs had dumped a vast block of Maxwell Communications stock on October 31, a sale which was to become public on November 5, and which would almost certainly set off a stampede by other sellers.

Joe Haines, Maxwell’s confidant and official biographer, had lunch with him and a group of Mirror editors on October 31, six days before Maxwell died. “He was not crumbling under the pressure,” the still-loyal Haines insisted. “He was relaxed. He was enjoying his food. He wanted to raise the price of the paper, but he accepted our objections.”

His daughter Ghislaine visited him in his office before he flew off to Gibraltar. “He was looking for an apartment in New York—a sort of pied-à-terre, where he could talk and have meetings—and he wanted me to help him,” she said. “He asked me to go see a particular apartment. He said, ‘If you like it, I’ll make time to see it and come to New York.’ ”

The next time Ghislaine saw her father, he was dead. His body had been spotted in the Atlantic Ocean—floating face up, its eyes wide open—by an air-sea helicopter rescue team from Gando airport. At first, the crew harnessed Maxwell to the end of a winch and tried to raise him out of the water. But he was too heavy, and the effort may have left abrasions on his skin and torn muscle tissue in his shoulder and back, which were later discovered during an autopsy. Ultimately, the rescue team had to lower a stretcher and tie the body to that.

Photographs and fingerprints were taken, and when Betty Maxwell arrived, she was asked to identify the body. She looked down at the remains of her sixty-eight-year-old husband and nodded her head. “His face was totally smooth and serene,” she later told a close friend, contradicting speculation that he had been beaten and had his nose broken. “He looked more handsome than at any time in recent years.” Her son Philip covered his face with his hand.

By Wednesday, November 6, the family had hired a local Spanish lawyer, and Betty Maxwell was putting pressure on him to get her husband’s body released so that it could be buried, according to Jewish ritual, as quickly as possible. Maxwell had made plans to be interred in a grave on the Mount of Olives, overlooking the Old City of Jerusalem. The Mount of Olives was more than a place of honor; according to Jewish tradition, its graves would be opened before any others by God on Judgment Day. Betty was eager to have Maxwell’s body flown to Israel and turned over to the religious authorities before sundown on Friday, the start of the Jewish Sabbath.

Under this pressure, Spanish pathologists worked feverishly through the day and night to eviscerate and embalm Maxwell’s body. They placed his body parts— heart, lungs, liver, and other internal organs—in three ice chests, and shipped them off to Madrid for a postmortem. They then issued a death certificate, declaring that Maxwell had died of “heart and lung failure.” (A later, equally inconclusive Spanish autopsy report cited heart disease and drowning as possible contributing factors.)

Because of his great bulk, Maxwell’s massive coffin would not fit through the door of his private Gulfstream IV, so a larger jet was chartered in Switzerland. By the time Betty Maxwell arrived in Israel on Friday with the body, the world press was aflame with speculation about a possible cover-up of the real cause of Maxwell’s death. Dr. Iain West, an eminent British pathologist appointed by the insurers of the Lloyd’s of London syndicate, flew to Israel to conduct his own postmortem at the L. Greenberg Institute of Forensic Medicine, which is affiliated with the Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University. He was assisted by his wife, Dr. Vesna Djurovic, who is also a physician, and three Israeli pathologists. Afterward, West proceeded to Madrid to haggle with the Spaniards until they finally let him examine Maxwell’s body parts, and to study their five-hundred-page autopsy report.

Most people in Britain were convinced that Maxwell had taken his own life. “He realized things were coming to a thunderous conclusion, and he finally confronted his own mortality,” said Peter Thompson, the co-author, along with Anthony Delano, of Maxwell: A Portrait of Power. Roy Greenslade agreed. “He knew he faced jail, and he decided to jump.” “I’ve known him for twenty-five years,” said Nigel Dempster, Britain’s leading gossip columnist, “and what he couldn’t stand was ridicule and being exposed. He had treated people abominably, and if he lived, everybody would have been at him. I think he caused his own death by inducing a heart attack by thrashing around in the water. ”

Tom Bower, the author of Maxwell: The Outsider and the acknowledged expert on the man, didn’t see it that way. “The only thing the pathologists knew for certain,” he said, “is that Maxwell had taken some seasick tablets and vomited at some stage before he went into the water. The suicide theory depends on his jumping into the water while conscious.”

Many of Maxwell’s friends and associates rejected suicide outright. Maxwell, they said, had wriggled out of far worse fixes before. “Suicide is the last thing a traditional Jew would do,” said Arthur Schneier, a prominent New York rabbi. “People who commit suicide are considered outcasts. Mourning is not permitted for them. They must not be buried in that part of a Jewish cemetery that consists of hallowed ground.”

In the opinion of those familiar with the contents of the autopsy conducted by Dr. West, the mystery surrounding Maxwell’s death would be swept away by the eventual release of the official Israeli postmortem and Dr. West’s report. Those people pointed out that the bloodstains, discoloration, and injuries found on Maxwell’s body by the pathologists in Tel Aviv were all probably caused by the rough handling of his body after he died and by the postmortem evisceration in Spain.

The Israeli report, which ran to about fifteen pages and was written in English, said that, in the opinion of the pathologists, Maxwell’s death was most probably caused by drowning. It went on to assert that the examination of the body indicated a compatibility with an involuntary fall into the sea, and that there were blunt injuries on the body, caused prior to death. Betty Maxwell herself told me the report concluded that her husband was alive when he fell into the water. “They found he had large tears in his left shoulder that were concurrent with his hanging by his left arm to save himself,” she said.

Another finding—compiled by the London station of the Central Intelligence Agency—added further credence to this interpretation, according to one source; it stated that Maxwell was not murdered, but rather fell into the water after suffering some kind of seizure, probably attributable to his bad heart.

Meanwhile, however, in the absence of any public statement, the Maxwell mystery only seemed to grow by the day. Rumors that he had been an agent of Mossad were fueled by his extraordinary funeral in Jerusalem, which was attended by Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir and practically the entire political and business establishments. No less a figure than Chaim Herzog, the president of the state of Israel, delivered the eulogy.

I asked Teddy Kollek, the mayor of Jerusalem and an old friend of mine, to explain to me why Maxwell had been accorded such an honor. “There are several explanations,” Kollek said. “Herzog served with Maxwell in the same unit in the British Army at the end of World War II. Although Maxwell never gave much to charity, he did contribute to Herzog’s president’s fund, which is used to help people out. Maxwell also created a lot of connections in Russia to smooth the way for Jewish emigration. And he invested in Israel and made a big profit when he sold his businesses, and Israelis hoped that he would be seen as an example and attract other investors.”

The report compiled by the C.I.A. station in London allegedly concluded that, although Maxwell had cooperated informally with Mossad by passing on information, he was not an agent. And Peter Jay, the former British ambassador, threw cold water on the theory that Maxwell had been a spy for Mossad—or for any other intelligence agency, for that matter. “Before I took the job with him,” Jay told me, “I did, as any sensible member of the British establishment would have, what is called taking soundings. Speaking very privately, I said that I had been asked to take this employment with Robert Maxwell, and was giving serious thought to doing so. Was there anything I ought to know? Provided you’re a person in whom they have confidence, they will find a way to discourage you if they think it’s a bad idea. And in that sense, I got an all-clear.

“I was quite clear in my mind,” he continued, “if any part of the British government service concerned with international affairs would have thought there was some reason of propriety, prudence, or loyalty, as a former ambassador, I would have gotten the appropriate signal not to take the employment. And, I repeat, I did not…. I find it inconceivable that Mossad, with its awesome reputation for efficiency and ruthlessness, would want to have anything to do with this crazy guy, who never took guidance from anybody. What explains the quasi-state funeral they gave him? Money! He bought the bloody plot on the Mount of Olives.”

“When Maxwell turned sixty,” recalled Robert Hodes, co-chairman of the law firm Willkie Farr & Gallagher, “Betty wanted to produce a Festschrift, or holiday book, and she wrote hundreds of people throughout the world, including people such as myself, who had been on the other side of battles against her husband. I, for instance, had represented Saul Steinberg in the famous Pergamon case in the late sixties and early seventies that almost destroyed Maxwell. Betty wrote something like ‘I know you were his enemy for a number of years and saw the worst in him, but I have reason to believe that you never hated him. Is there something you can say to include in the Festschrift?’

“Now, all my pals refused her request,” continued Hodes, “but I wrote a brief thing, saying that what always had impressed me about Bob Maxwell was his extraordinary care and affection for his family. He really seemed to be someone devoted in an old-fashioned and traditional way to a family, not the way I’ve seen with other tycoons and their families.”

What made Hodes’s recollection so poignant was that it now appeared that Maxwell had destroyed his family, and, in particular, had victimized Kevin and Ian. For within less than a month of their father’s funeral, Kevin and Ian Maxwell were fighting for their lives. They were forced to resign all their directorships in the public companies. Their assets were frozen. Kevin’s house was put up for sale, as were the Lady Ghislaine and the Gulfstream IV. Their passports were seized. They were hauled before a parliamentary committee, where they refused to testify on the ground that it might incriminate them. And Kevin, the son of a onetime billionaire, was placed by a judge on short rations—receiving an allowance of $2,650 a week.

Investigations were under way to discover if they had aided their father in his illegal diversion of resources. In London, the Financial Times claimed that Kevin and Ian had, in fact, authorized loans and transfers of funds from the Mirror Group pension funds to the private companies. In America, more than one informed source told me that the brothers had also continued to shuffle around Berlitz stock even after their father was gone. “No one is ever reconciled to going to jail, but Kevin has certainly accepted the strong possibility that he will go to jail,” said a banker who had been on intimate terms with the Maxwells, and who had talked to Kevin in the weeks after his father’s death.

This, then, was the final Maxwell mystery: How could a man who was so devoted to his family ensnare his own flesh and blood in his illegal acts? And why had his sons apparently allowed themselves to become involved?

The answers to both of those questions lay in the psychological hold that Maxwell exercised over his children. Of all seven, Philip, it seemed, had suffered the most. “He suffered a nervous breakdown at one stage of his life,” said Roy Greenslade, the former Mirror editor. “He went off to Argentina in the late seventies, and while he was there, he met a woman named Nilda, who had a child, and they fell in love, and he married her. Maxwell was incredibly enraged, and a massive argument began. I saw Philip once in Maxwell’s office, and he had tears in his eyes, and his face was pressed into his father’s arms. I said, ‘Philip, you’re not looking too well,’ but he wouldn’t enter into any discussion.”

A year after Philip was born, in 1950, Betty Maxwell gave birth to twin girls— Christine and Isabel. “Isabel,” said Greenslade, “had had a very unhappy marriage, and then she got married last Christmas. Maxwell didn’t go to the wedding. It was typical of him, failing to turn up even for his child’s wedding. I said to him, ‘I see you didn’t turn up for her wedding,’ and he said, ‘I meant to, but, after all, it was her second.’ ”

“Bob was, in a way, hard on his children,” Betty Maxwell conceded. “When they were growing up, they asked me how should they deal with Dad. I would say to Bob, ‘Would you consider this angle or that angle?’ I would never be disloyal by saying to the children, ‘Daddy’s wrong.’ If he was angry, I wouldn’t permit them to play one parent off against the other.”

And it was his monumental anger—an anger that had burned deeply within him since the day he had cut off his payess in his native Czech shtetl—that he used to control his sons. “However bad it was for those of us who worked for him,” said Susan Heilbron, who was employed for a brief time in America as vice president and general counsel at the Maxwell Macmillan Group, “it was worse for the children. Maxwell would get Kevin on the speakerphone, and, in front of everybody else, he’d scream at him and berate him, using the foulest language.”

“No one can understand the enormous pressure he put his sons under,” said Nick Davies, who was fired last fall as foreign editor of the Daily Mirror when he was accused of running guns for Israel (a charge he denied) and lying about his meeting with an American arms dealer. “He bullied them. He castigated them. He told them they were no good, to fuck off. When he said ‘Sign,’ they signed!”

“His sons were in mortal fear of their father,” said Maxwell biographer Peter Thompson. “Mike Molloy, the [former] editor of the Mirror, used to have a seven-card-stud game in the office after work. It started at eleven o’clock at night. Ian joined it. We proceeded to take a lot of money off of Ian. He lost all his money and had to write a check. ‘Please don’t tell my father—I don’t want him to know about this,’ Ian told us. He couldn’t be seen by his father as a loser. They were Maxwells, and the boys had to live up to their father’s image.”

Ian, Kevin, and Ghislaine were born within five years of one another, played together as children, and remained very close. Their bond was strengthened by their mutual hatred of Jean Baddeley, the woman who for more than twenty years was closest to their father. Until the mid-eighties, Jean Baddeley was Maxwell’s personal assistant, office manager, and traveling companion. “She totally sacrificed herself to Maxwell,” said Nick Davies, “and she was hated for it by the children of his marriage, because they felt this woman was taking away their father.”

“I cannot overstate his personal control over his children,” said one of his attorneys. “But the boys didn’t really know what was going on. Until about a year ago, Bob had compartmentalized his family. But when he perceived that everything was falling apart, he did what desperate men do—anything to stay alive.”

Yet there was no doubt that his sons still loved him. “Ian phoned me after Bob died to find out how I was feeling,” Joe Haines recalled. “He said to me, ‘Bob’s left us in a hell of a mess. But he’s still my father.’ ”

The one hit hardest by his death was Ghislaine, who recently turned thirty. I visited her in her New York apartment shortly before Christmas. She was dressed in a pair of jeans and a loose shirt, and she wasn’t wearing any makeup. The floor was strewn with newspaper clippings about her father. Hundreds of letters of condolence lay on her desk, along with boxes of cards of acknowledgment waiting to be sent in reply.

I did not recognize in Ghislaine Maxwell the young woman her friends had described to me—the racy, glamorous social flibbertigibbet whom George Hamilton had escorted to the Ever Ready Derby in England and skied with in Aspen, who had attended the Kerry Kennedy-Andrew Cuomo wedding, and who had once instructed her father’s pilot to put his helicopter into a free-fall to scare her fellow passenger.

“He wasn’t a crook,” she told me. “A thief to me is somebody who steals money. Do I think that my father did that? No. I don’t know what he did. Obviously, something happened. Did he put it in his own pocket? Did he run off with the money? No. And that’s my definition of a crook.

“I’m surviving—just,” she went on. “But I can’t just die quietly in a comer. I have to believe that something good will come out of this mess. It’s sad for my mother. It’s sad to have lost my dad. It’s sad for my brothers. But I would say we’ll be back. Watch this space.”