The Intelligence of Plants

By Cody Delistraty, published on The Paris Review, on September 26, 2024

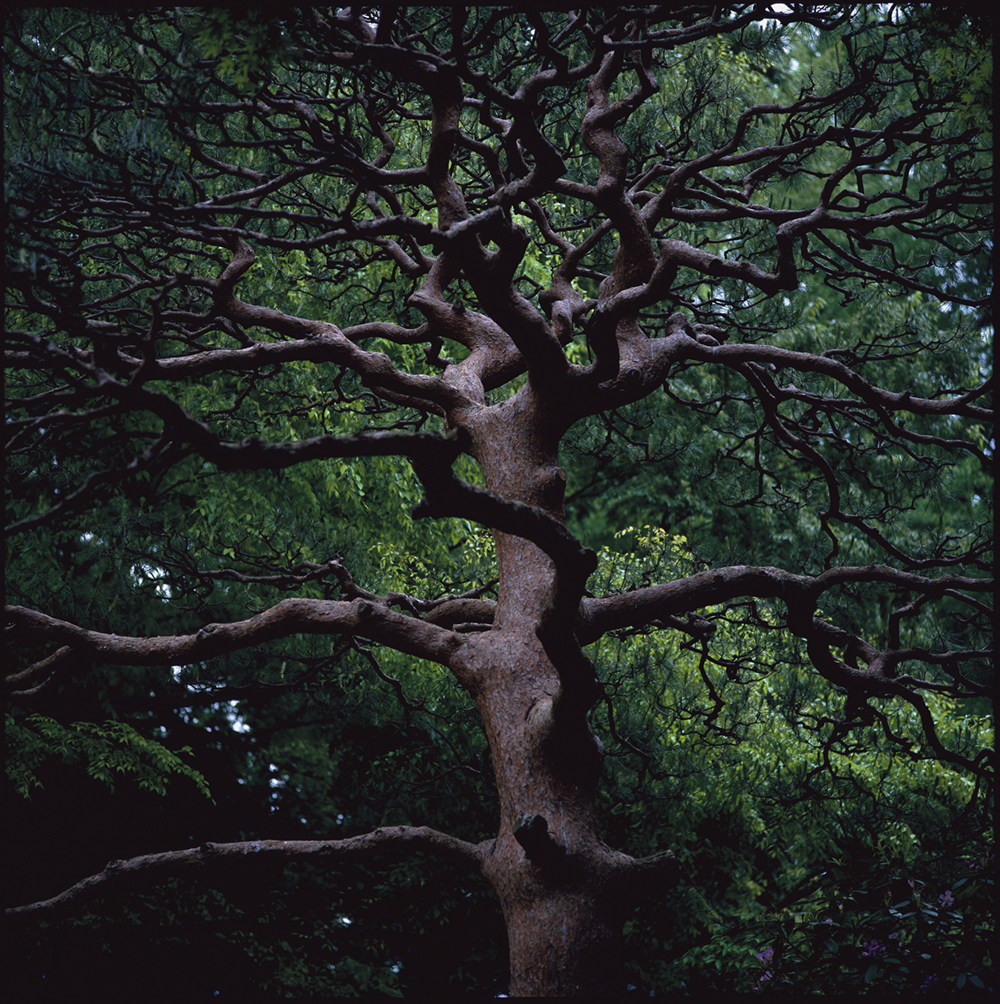

Miguel Rio Branco, Untitled, Tokyo, 2008 © Miguel Rio Branco

A few years ago, Monica Gagliano, an associate professor in evolutionary ecology at the University of Western Australia, began dropping potted Mimosa pudicas. She used a sliding steel rail that guided them to six inches above a cushioned surface, then let them fall. The plant, which is leafy and green with pink-purple flower heads, is commonly known as a “shameplant” or a “touch-me-not” because its leaves fold inward when it’s disturbed. In theory, it would defend itself against any attack, indiscriminately perceiving any touch or drop as an offense and closing itself up.

The first time Gagliano dropped the plants—fifty-six of them—from the measured height, they responded as expected. But after several more drops, fewer of them closed. She dropped each of them sixty times, in five-second intervals. Eventually, all of them stopped closing. She continued like this for twenty-eight days, but none of them ever closed up again. It was only when she bothered them differently—such as by grabbing them—that they reverted to their usual defense mechanism.

Gagliano concluded, in a study published in a 2014 edition of Oecologia, that the shameplants had “remembered” that their being dropped from such a low height wasn’t actually a danger and realized they didn’t need to defend themselves. She believed that her experiment helped prove that “brains and neurons are a sophisticated solution but not a necessary requirement for learning.” The plants, she reasoned, were learning. The plants, she believed, were remembering. Bees, for instance, forget what they’ve learned after just a few days. These shameplants had remembered for nearly a month.

The idea of a “plant intelligence”—an intelligence that goes beyond adaptation and reaction and into the realm of active memory and decision-making—has been in the air since at least the early seventies. A shift from religion to “spirituality” in the sixties and seventies unlocked new avenues of belief, and the 1973 bestseller The Secret Life of Plants catalyzed the phenomenon. Written by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird, the book made some wildly unscientific claims, such as that plants can “read human minds,” “feel stress,” and “pick out” a plant murderer. Mostly, it proved to be a touchstone.

Wrapped in pseudoscience, these claims, the authors said, were “proven” by “experiments.” Cleve Backster, a polygraph tester for the CIA, did one such experiment in 1966 when, “on a whim,” he attached a galvanometer (a machine that registers electrical currents) to a dracaena, a tropical palm houseplant. Silently, Backster imagined the plant was on fire. The galvanometer flickered. Backster concluded the plant was feeling stress from his thoughts. “Could the plant have been reading his mind?” ask Tompkins and Bird in the book. In another experiment, Backster had a friend stomp on a plant. Then, that friend and five other human “suspects” walked out in front of the plant that had “witnessed” the stomping. The plant was hooked up to a galvanometer. When the killer entered the room, the plant sent out a wave of electricity, thereby “identifying” the murderer.

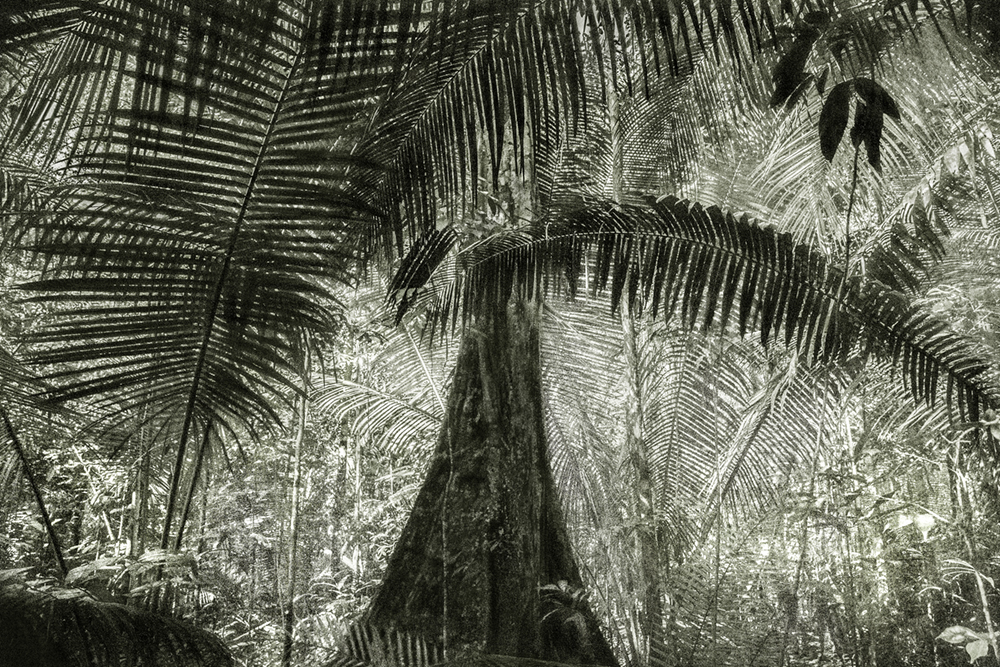

Cássio Vasconcellos, A Picturesque Voyage Through Brazil, #28, Courtesy of the artist, Gadcollection, and Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo © Cássio Vasconcellos

Richard Fortey, a former professor of paleobiology at Oxford and paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, scorns the idea of “smart plants.” “It’s so anthropomorphized that it’s really not helpful,” he told Smithsonian. “Trees do not have will or intention. They solve problems, but it’s all under hormonal control, and it all evolved through natural selection.” These “magical” notions of plant intelligence are worrisome, he says, because people “immediately leap to faulty conclusions, namely that trees are sentient beings like us.”

But while it is easy to dismiss lonely men conducting electrical experiments on their houseplants and savvy authors taking advantage of a gullible public, there may, in fact, be some truth to the idea.

Darwin floated the first modern ideation of plant intelligence in 1880. Writing in The Power of Movement in Plants, he concluded that the root of a plant has “the power of directing the movements of the adjoining parts” and thus “acts like the brain of one of the lower animals; the brain being seated within the anterior end of the body, receiving impressions from the sense organs and directing the several movements.” Darwin was talking about how plants react to shifts in vibrations, sounds, touch, humidity, and temperature—but these are just adaptive reactions. Facing toward the sun or closing at a touch does not require quasi-neurological abilities. There is no processing or choice involved—unlike the apparent memory shown by Gagliano’s experiment. (Many of the Ancient Greeks—like Plato, Anaxagoras, Democritus, and Empedocles—shared the belief that plants have a kind of brain where sensitivities could be “processed.”)

Cássio Vasconcellos, A Picturesque Voyage Through Brazil, #37, Courtesy of the artist, Gadcollection, and Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo © Cássio Vasconcellos

Recently, more findings have seemed to support—or at least point toward—a more restrained version of plant intelligence. Plants may not be capable of identifying murderers in a lineup, but trees share their nutrients and water via underground networks of fungus, through which they can send chemical signals to the other trees, alerting them of danger. Peter Wohlleben, a forest ranger for the German government, has written extensively on trees, about diseases or insects or droughts. When Wohlleben came across a tree stump that had been felled probably half a millennium ago, he realized—scraping at it and seeing that it was still bright green beneath—that the trees around it had been keeping it alive, sending it glucose and other nutrients.

This plant communications system works similarly to the nervous system of animals. Trees can send out electrical pulse signals underground as well as signals through the air, via pheromones and gasses. When an animal, for instance, begins chewing on a tree’s leaves, the tree can release ethylene gas into the soil, alerting other trees, whereupon those nearby trees can send tannins into their leaves so that if they, too, get their leaves chewed, they might be able to poison the offending animal.

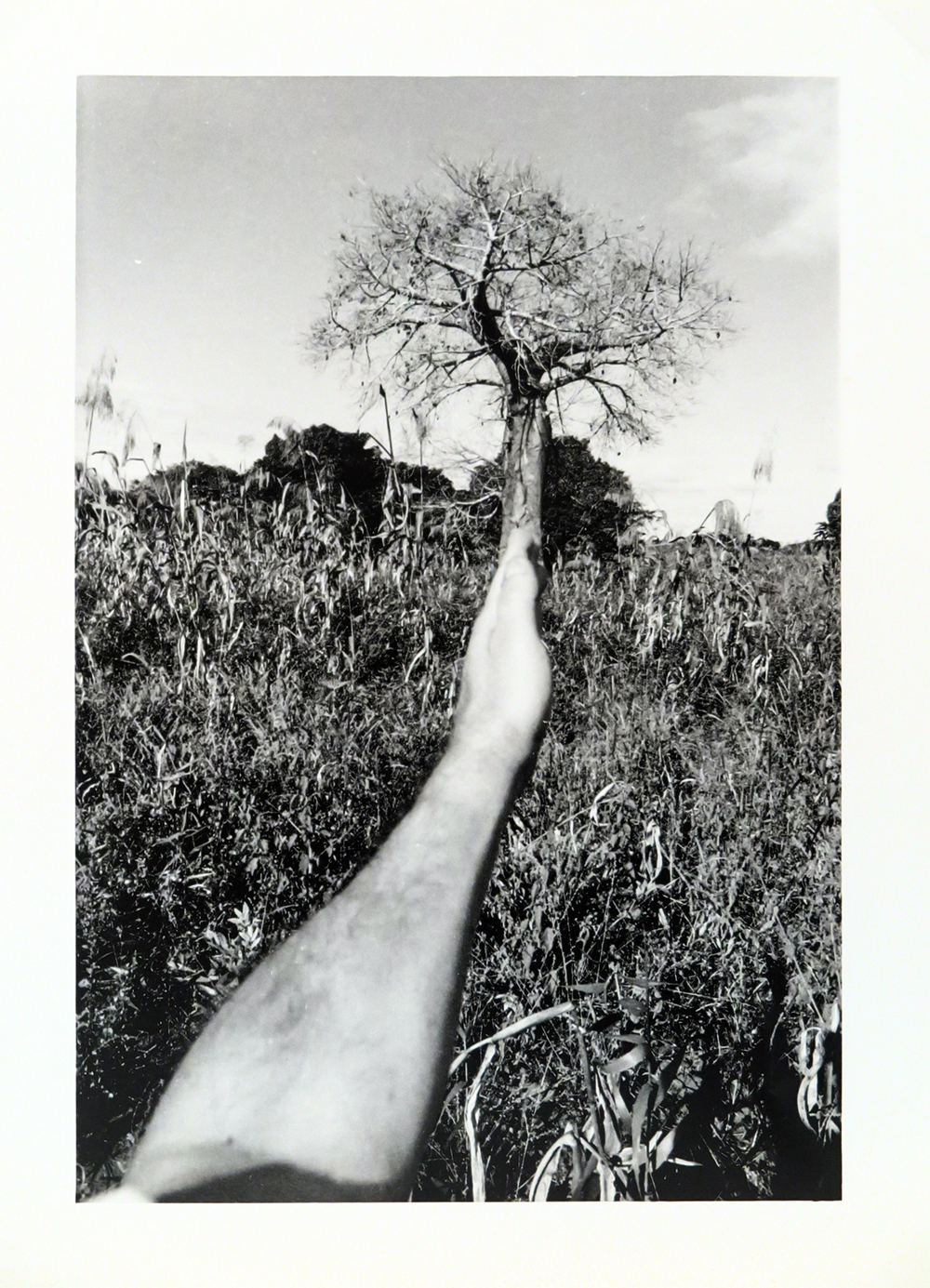

José Cabral Cabo Delgado, Tete, 2002. © José Cabral (Photo © Cyrille Martin)

Trees can differentiate between threats, as well. They respond differently to a human breaking off one of its branches than they do to an animal eating at them—with the former, it will try to heal; with the latter, it will try to poison. Plants even share space with one another. In a 2010 study, when four Cakile edentula, or “sea-rocket plants,” were put in the same pot, they shared their resources, moving their roots to accommodate the others. If the plants were just acting evolutionarily, it would follow that they would compete for resources; instead, they seem to be “thinking” of the other plants and “deciding” to help them.

Even the slightest possibility of a proven plant intelligence would have massive scientific and existential implications. If plants can “learn” and “remember,” as Gagliano believes, then humans may have been misunderstanding plants, and ourselves, for all of history. The common understanding of “intelligence” would have to be reimagined; and we’d have missed an entire universe of thought happening all around us.

On a recent afternoon in Paris, I felt particularly disconnected from nature. Across the street from the hulking glass facade of the Fondation Cartier is the famous, and very green, Montparnasse Cemetery. But the historical humans beneath its grounds, like Charles Baudelaire and Simone de Beauvoir, define the space far more than any of its plant life.

The exhibition “Nous Les Arbres” (“We the Trees”) at the Fondation Cartier attempts to show that humans are a just small part of a world that belongs to plants. (Plants, after all, make up about 99 percent of earth’s biomass.) There are installations of herbariums with bits of trash scattered throughout, videos of countryside pensioners discussing their favorite trees and how they care for them, and massive jungle canvases by the Brazilian painter Luiz Zerbini. Nearly every appeal to nature, however, evokes only a sense of alienation. The older people fawning over their favorite trees come off as fanatics with hyperniche interests, and the installations showing the human impact on the environment are so distressingly common that it’s difficult to engage with them as if for the first time. More than anything, the exhibition accidentally proves that humans are so accustomed to viewing ourselves as fundamentally separate—even insulated—from the environment that we must make a museum show within a major urban capital to try to reconnect with it.

Sebastián Mejía, Série Quasi Oasis, 17, Santiago du Chili, 2012 © Sebastián Mejía

A notable exception: In the Chilean photographer Sebastian Mejia’s black-and-white images, trees burst through houses and gas station roofs in Santiago. A massive palm grows in the middle of a car dealership. A tilted pine threatens to crash onto a street. Similarly shocking is a film called EXIT by the architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, which shows the destruction of major forests. These works succeed because they make no attempt to appeal. Instead, they accost the viewer with nature’s power and its fragility. Our houses, stores, and filling stations can be overrun and destroyed by a single palm; a centuries-old forest can be decimated by a single fire. Our lack of respect for nature is at once astounding and ordinary. It allows us to remain in the comforts of late-stage capitalism. If we were to be honest with ourselves about our individual capacity for harm, we would no longer eat meat, live in big homes, drive cars, use plastic water bottles or bags. But rather than numbing ourselves, we might at least allow ourselves to feel some pain at our complicity. Over the long-term, this might push us toward change.

If we respected nature more—the power it has to not only be destroyed by us but to destroy us in turn—would we see more clearly how imbricated we are? Would we be more hesitant about growing plants in monocultures, genetically manipulating them for our pleasure, destroying forests? Would we try harder to protect the environment, if we understood that by protecting plants and trees we are protecting ourselves?

If plants can learn, as Gagliano suggests, they may be able to slowly adapt to fight climate change on their own, adopting and passing down traits of hardiness, stockpiling nutrients, sharing and alerting. This kind of learning would, in a way, be the ultimate intelligence: the ability to actively reshape their existence in order to survive.

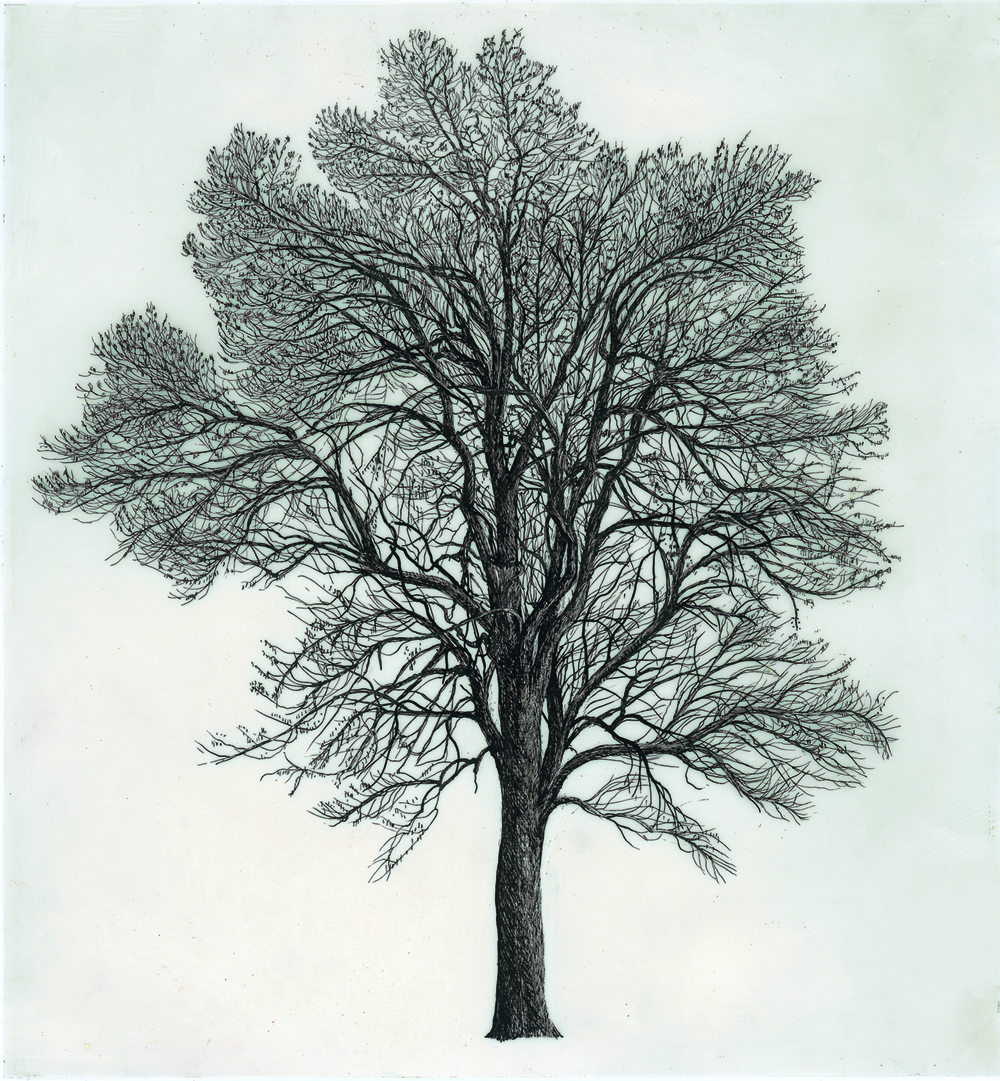

Cesare Leonardi and Franca Stagi, Fraxinus excelsior L , 1963-1982 © Cesare Leonardi and Franca Stagi

Intelligence is really the central question in all of this. What, precisely, is it? Must the ability to remember, learn, and decide come from neurons and a “brain,” as we tend to think of it, or should we broaden the definition to include a “mindless mastery,” as Anthony Trewavas, an emeritus professor of biological sciences at the University of Edinburgh, calls it? The crux of the question rests on whether we think we are the center of the universe and that our mechanisms for remembering and learning, are superior. Or, might we be willing to see that there are other, nonneurological modes of thought? Might we be willing to de-center ourselves and view the environment through a nonhuman lens?

Plants, as Gagliano concluded, might have a far greater sentience than we’d ever thought possible. The implications of plants that “remember” being dropped and “decide” it’s safe to not protect themselves aren’t best expressed in anthropomorphic terms, but we don’t yet have other language. In truth, we know so little even about ourselves; our science cannot fully explain how humans learn and remember. Why not consider that plants have been doing the same for far longer than we have been around, with an intelligence that is radically different from ours?

Cody Delistraty is a writer and critic in Paris and New York.