How The CIA Used Brain Surgery To Make Six Remote Control Dogs

Newly released files from “behavior modification,” or mind control, projects conducted as part of the infamous Project MKUltra reveal the CIA experimented in more than controlling humans with psychotropic drugs, electrical shocks and radio waves—they also created field operational, remote-controlled dogs.

The documents were provided under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) by John Greenewald, founder of The Black Vault, a site specializing in declassified government records. In one declassified letter (released as file C00021825) a redacted individual writes to a doctor (whose name has also been redacted) with advice about launching a laboratory for experiments in animal mind control. The writer of the letter is already an expert in the field, whose earlier work had culminated with the creation of six remote control dogs, which could be made to run, turn and stop.

“As you know, I spent about three years working in the research area of rewarding electrical stimulation of the brain,” the individual writes. “In the laboratory, we performed a number of experiments with rats; in the open field, we employed dogs of several breeds.”

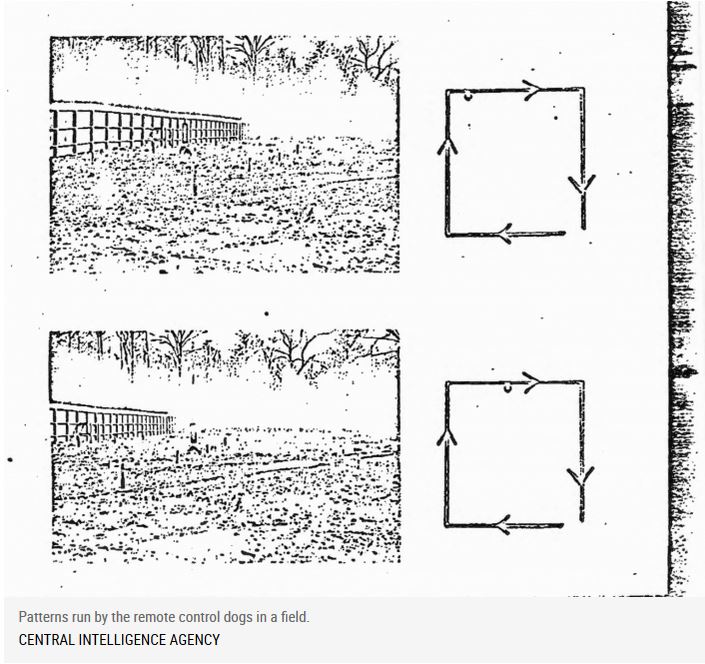

The letter writer characterizes the work with remote-controlling dogs as a success, describing “a demonstrated procedure for controlling the free-field behaviors of an unrestrained dog.”

Attached to the letter is the writer’s final report from his earlier research, published in 1965, titled “Remote Control Behavior with Rewarding Electrical Stimulation of the Brain,” with the principle investigator’s name redacted.

“The specific aim of the research program was to examine the possibility of controlling the behavior of a dog, in an open field, by means of remotely triggering electrical stimulation of the brain,” the report states. “Such a system depends for its effectiveness on two properties of electrical stimulation delivered to certain deep lying structures of the dog brain: the well-known reward effect, and a tendency for such stimulation to initiate and maintain locomotion in a direction which is accompanied by the continued delivery of stimulation.”

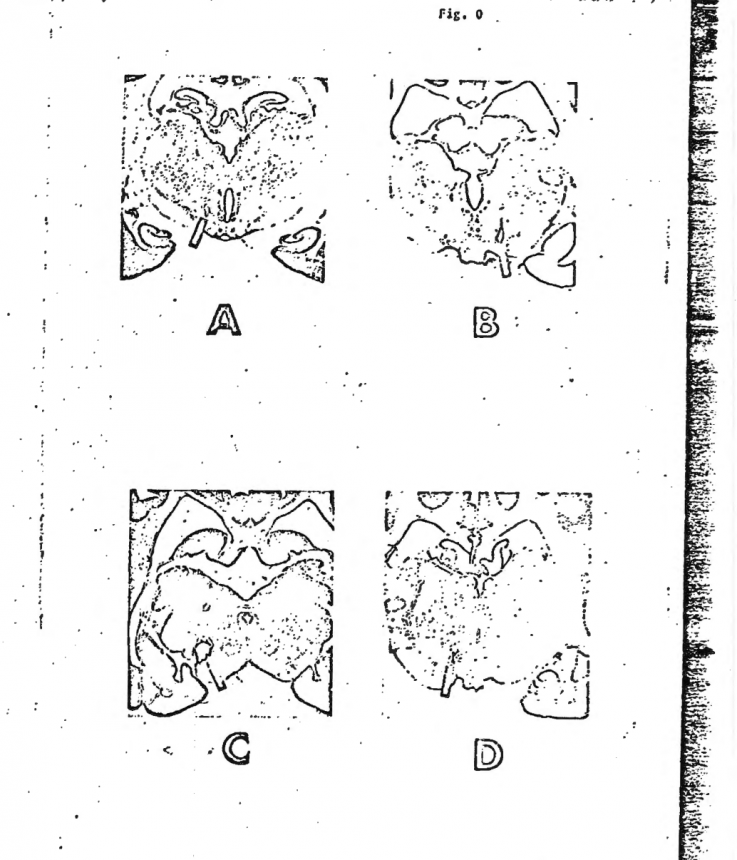

Delivering that electrical stimulation to a dog’s brain involved some gruesome side effects, including “infection at the electrode site due to a failure of the surgical wound to heal.”

After trying out a plastic helmet, they instead settled on a new surgical technique that involved, “embedding the electrode entirely within a mound of dental cement on the skull and running the leads subcutaneously to a point between the shoulder blades, where the leads are brought to the surface and affixed to a standard dog harness.”

After implanting electrodes deep in the subject dog’s brain, a battery pack and stimulator was added to the harness, through which signals could be sent to the electrodes. “The stimulator had to be reliable and capable of sufficient voltage output to be usable in the face of expected impedance variation across individual dogs.”

At least by 1967, when the letter was written, it seems unlikely that remote-controlled dogs were ever used in the field, as the letter writer outlines some of the limitations and challenges to any follow-up program going forward.

“Behavioral control was limited to distances of 100 to 200 yards, at most,” they write in the letter. Other concerns are more mundane, such as the letter’s speculation regarding where the CIA might find a “suitable open field” nearby.

Still, the prospect of a potential new laboratory seems to fire the letter writer’s imagination, who describes potential experimentation on “a range of species,” should they want to move past “basic research, i.e., rat work.”

C00021825 is far from the only “Behavioral Modification” document released by The Black Vault involving animals. Numerous other files pertain to budgeting and acquisition for animal experimentation. One file (which has been previously declassified) details, with heavy redactions, the practical possibilities of training and equipping cats for “foreign situation” field work.