Vote rigging: How to spot the tell-tale signs

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesGabon’s opposition says it was cheated of victory, after official results showed a turnout of 99.93% in President Ali Bongo’s home region, with 95% of votes in his favour. Elizabeth Blunt has witnessed many elections across Africa, as both a BBC journalist and election observer and looks at six signs of possible election rigging.

Too many voters

Watch the turnout figures ‒ they can be a big giveaway.

You never get a 98% or 99% turnout in an honest election. You just don’t.

Voting is compulsory in Gabon, but it is not enforced; even in Australia where it is enforced, where you can vote by post or online and can be fined for not voting, turnout only reaches 90-95%.

The main reason that a full turnout is practically impossible is that electoral registers, even if they are recently compiled, can rarely be 100% up-to-date.

Even if no-one gets sick or has to travel, people still die. And when a register is updated, new voters are keen to add themselves to the list.

No-one, however, has any great enthusiasm for removing the names of those who have died, and over time the number of these non-existent voters increases.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesI once reported on an election in the Niger Delta where some areas had a turnout of more than 120%.

“They’re very healthy people round here, and very civic-minded,” a local official assured me.

But a turnout of more than 100%, in an area or an individual polling station, is a major red flag and a reason to cancel the result and re-run the election.

A high turnout in specific areas

Even where the turnout is within the bounds of possibility, if the figure is wildly different from the turnout elsewhere, it serves as a warning.

Why would one particular area, or one individual polling station, have a 90% turnout, while most other areas register less than 70%?

Something strange is almost certainly going on, especially if the high turnout is an area which favours one particular candidate or party over another.

Large numbers of invalid votes

There are other, more subtle ways that riggers can increase votes ‒ or reduce them.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesKeep an eye on the number of votes excluded as invalid. Even in countries with low literacy rates this isn’t normally above 5%.

High numbers of invalid votes can mean that officials are disqualifying ballots for the slightest imperfection, even when the voter’s intention is perfectly clear, in an attempt to depress votes for their opponents.

More votes than ballot papers issued

When the polls close, and before they open the boxes, election officials normally have to go through a complicated and rather tedious process known as the reconciliation of ballots.

After they have counted how many ballot papers they received in the morning, they then need to count how many are left, and how many ‒ if any ‒ were torn or otherwise spoiled and had to be put aside.

The result will tell them how many papers should be in the box. It should also match the number of names checked off on the register.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesThe first task when the box is opened is to count the number of papers inside, this is done prior to counting the votes for the different candidates.

If there is a discrepancy, something is wrong. And if there are more papers in the boxes than were issued by the polling staff, it is highly likely that someone has been doing some “stuffing”.

That’s a good enough reason to cancel the result and arrange a re-run.

Results that don’t match

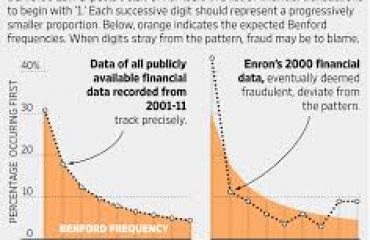

Mobile phones have made elections much more transparent.

It is now standard practice to allow party agents, observers and sometimes even voters to watch the counting process and take photographs of the results sheet with their phones.

They then have proof of the genuine results from their area ‒ just in case the ones announced later by the electoral commission don’t match.

It has clearly taken crooked politicians some time to catch up with the fact that people will now know if they change the results.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesIn south-eastern Togo, local party representatives told me that they witnessed the count in 2005 and endorsed the result; they saw the official in charge leave for the capital, taking the signed results sheet with him. Yet the results announced later on the radio were different.

The same thing happened in Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2011. The results announced on the radio were not the same as those international observers saw posted outside the polling stations.

But this transparency only works if the official announcement of results includes figures for individual counting centres ‒ and this has become an issue in the current Gabonese election.

Delay in announcing results

Finally something that is not necessarily a sign of rigging, but it is often assumed to be so.

Election commissions, particularly in Africa, can appear to take an inordinately long time to publish official results.

This is not helped by local observer networks and political parties who, tallying up the results sent in by their agents on mobile phones, have a good idea of the result long before the more cumbersome official process is completed.

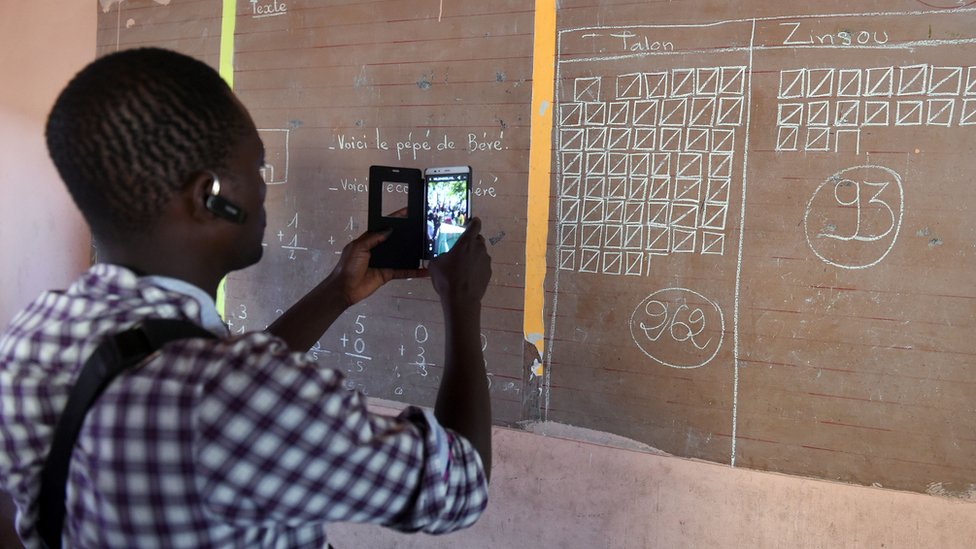

But the official process takes time, especially in countries with poor communications, and the introduction of modern electronic transmission systems has not necessarily helped.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesWhere these systems have proved too demanding for the context, as in Malawi last year, they can actually increase delays as staff struggle to make the technology work.

In that particular case the results eventually had to be transmitted the old fashioned way; placed in envelopes and driven down to the capital under police escort.

By then, allegations of rigging were flying.

Delay is certainly dangerous, fuelling rumours of results being “massaged” before release and increasing tensions, but this is not incontrovertible proof of rigging.