Army Is Spending Half a Billion to Train Soldiers to Fight Underground

U.S. Army leaders say the next war will be fought in mega-cities, but the service has embarked on an ambitious effort to prepare most of its combat brigades to fight, not inside, but beneath them.

Late last year, the Army launched an accelerated effort that funnels some $572 million into training and equipping 26 of its 31 active combat brigades to fight in large-scale subterranean facilities that exist beneath dense urban areas around the world.

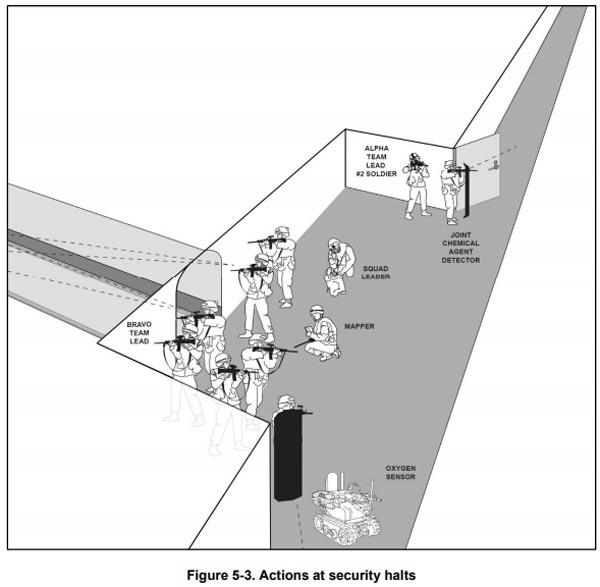

For this new type of warfare, infantry units will need to know how to effectively navigate, communicate, breach heavy obstacles and attack enemy forces in underground mazes ranging from confined corridors to tunnels as wide as residential streets. Soldiers will need new equipment and training to operate in conditions such as complete darkness, bad air and lack of cover from enemy fire in areas that challenge standard Army communications equipment.

Senior leaders have mentioned small parts of the effort in public speeches, but Army officials at Fort Benning, Georgia’s Maneuver Center of Excellence — the organization leading the subterranean effort — have been reluctant to discuss the scale of the endeavor.

“We did recognize, in a megacity that has underground facilities — sewers and subways and some of the things we would encounter … we have to look at ourselves and say ‘ok, how does our current set of equipment and our tactics stack up?'” Col. Townley Hedrick, commandant of the Infantry School at the Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence at Fort Benning, Georgia, told Military.com in an interview. “What are the aspects of megacities that we have paid the least attention to lately, and every megacity has got sewers and subways and stuff that you can encounter, so let’s brush it up a little bit.”

Left unmentioned were the recent studies the Army has undertaken to shore up this effort. The Army completed a four-month review last year of its outdated approach to underground combat, and published a new training manual dedicated to this environment.

“This training circular is published to provide urgently needed guidance to plan and execute training for units operating in subterranean environments, according to TC 3-20.50 “Small Unit Training in Subterranean Environments,” published in November 2017. “Though prepared through an ‘urgent’ development process, it is authorized for immediate implementation.”

A New Priority

The Army has always been aware that it might have to clear and secure underground facilities such as sewers and subway systems beneath densely-populated cities. In the past, tactics and procedures were covered in manuals on urban combat such as FM 90-10-1, “An Infantryman’s Guide to Combat in Built-up Areas,” dated 1993.

Before the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, the mission for taking large, underground military complexes was given to tier-one special operations units such as Army Delta Force and the Navy‘s SEAL Team 6, as well as the Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment.

But the Pentagon’s new focus on preparing to fight peer militaries such as North Korea, Russia and China changed all that.

An assessment last year estimates that there are about 10,000 large-scale underground military facilities around the world that are intended to serve as subterranean cities, an Army source, who is not cleared to talk to the press, told Military.com.

The Army’s Asymmetric Warfare Group — an outfit often tasked with looking ahead to identify future threats — told U.S. military leaders that special operations forces will not be able to deal with the subterranean problem alone and that large numbers of conventional forces must be trained and equipped to fight underground, the source said.

The endeavor became an urgent priority because more than 4,800 of these underground facilities are located in North Korea, the source said.

Relations now seem to be warming between Washington and Pyongyang after the recent meeting between U.S. President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. But in addition to its underground nuclear missile facilities, North Korea has the capability to move thousands of troops through deep tunnels beneath the border into South Korea, according to the Army’s new subterranean manual.

“North Korea could accommodate the transfer of 30,000 heavily armed troops per hour,” the manual states. “North Korea had planned to construct five southern exits and the tunnel was designed for both conventional warfare and guerrilla infiltration. Among other things, North Korea built a regimental airbase into a granite mountain.”

For its part, Russia inherited a vast underground facilities program from the Soviet Union, designed to ensure the survival of government leadership and military command and control in wartime, the manual states. Underground bunkers, tunnels, secret subway lines, and other facilities still beneath Moscow, other major Russian cities, and the sites of major military commands.

More recently, U.S. and coalition forces operating in Iraq and Syria have had to deal with fighters from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria operating in tunnel systems.

Learning to Fight Underground

To prepare combat units, the Army has activated mobile teams to train the leadership of 26 brigade combat teams on how prepare units for underground warfare and plan and execute large-scale combat operations in the subterranean environment.

So far, the effort has trained five BCTs based at Fort Wainwright, Alaska; Schofield Barracks, Hawaii; Camp Casey, Korea; and Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington. Army trainers have a January deadline to finish training 21 more BCTs located at bases including Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Fort Campbell, Kentucky; Fort Drum, New York; Fort Bliss and Fort Hood, Texas, and Fort Richardson, Alaska, the source said.

The 3rd BCT, 4th Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado is next in line for the training.

Army officials confirmed to Military.com that there is an approved plan to dedicate $572 million to the effort. That works out to $22 million for each BCT, according to an Army spokeswoman who did not want to be named for this article. The Army did not say where the money is coming from or when it will be given to units.

Army leaders launched the subterranean effort last fall, tasking the AWG with developing a training program. The unit spent October-January at Fort A.P. Hill, Virginia, developing the tactics, techniques and procedures, or TTPs, units will need to fight in this environment.

“Everything that you can do above ground, you can do below ground; there are just tactics and techniques that are particular,” the source said, adding that tactics used in a subterranean space are much like those used in clearing buildings.

“The principles are exactly the same, but now do it without light, now do it in a confined space … now try to breach a door using a thermal cutting torch when you don’t have air.”

Three training teams focus on heavy breaching, TTPs and planning and a third to train the brigade leadership on intelligence priorities and how to prepare for brigade-size operations in subterranean facilities.

“The whole brigade will be learning the operation,” the source said.

Army combat units train in mock-up towns known as military operations in urban terrain, or MOUT, sites. These training centers often have sewers to deal with rain water, but are too small to use for realistic training, the source said.

The Defense Department has a half-dozen locations that feature subterranean networks. They’re located at Fort Hood, Texas; Fort Story, Virginia; Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri; Camp Atterbury-Muscatatuck Urban Training Center, Indiana; Tunnel Warfare Center, China Lake, California and Yuma Proving Grounds, Arizona, according to the new subterranean training manual.

Rather sending infrastructure to these locations, units will build specially designed, modular subterranean trainers, created by the AWG in 2014. The completed maze-like structure is fashioned from 15 to 20 shipping containers, or conexes, and sits above ground.

Gen. Stephen Townsend, commander of Army Training and Doctrine Command, talked about these new training structures at the Association of the United States Army’s LANPAC 2018 symposium in Hawaii.

“I was just at the Asymmetric Warfare Group recently; they had built a model subterranean training center that now the Army is in the process of exporting to the combat training centers and home stations,” Townsend said.

“I was thinking to myself before I went and saw it, ‘how are we going to be able to afford to build all these underground training facilities?’ Well, they took me into one that wasn’t underground at all. It actually looked like you went underground at the entrance, but the facility was actually built above ground.But you couldn’t tell that once you went inside of it.”

Shipping containers are commonplace around the Army, so units won’t have to buy special materials to build the trainers, Hedrick said.

“Every post has old, empty conexes … and those are easily used to simulate working underground,” Hedrick said.

Specialized Equipment

Training is only part of the subterranean operations effort. A good portion of the $22 million going to each BCT will be needed buy special equipment so combat units can operate safety underground.

“You can’t go more than one floor deep underground without losing comms with everybody who is up on the surface,” Townsend said. “Our capabilities need some work.”

The Army is looking at the handheld MPU-5 smart radio, made by Persistent Systems LLC, which features a new technology and relies on a “mobile ad hoc network” that will allow units to talk to each other and to the surface as well.

“It sends out a signal that combines with the one next to it, and the one next to it … it just keeps getting bigger and bigger and bigger,” the source said.

Off the shelf, MPU-5s coast approximately $10,000 each.

Toxic air, or a drop in oxygen, are other challenges soldiers will be likely to face operating deep underground. The Army is evaluating off-the-shelf self-contained breathing equipment for units to purchase.

“Protective masks without a self-contained breathing apparatus provide no protection against the absence of oxygen,” the subterranean manual states. “Having breathing apparatus equipment available is the primary protection element against the absence of oxygen, in the presence of hazardous gases, or in the event of a cave-in.”

Soldiers can find themselves exposed to smoke, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, methane natural gas underground, according to the manual.

Breathing gear is expensive; some apparatus cost as much as $13,000 apiece, the source said.

Underground tunnels and facilities are often lighted, but when the lights go out, soldiers will be in total darkness. The Army announced in February that it has money in its fiscal 2019 budget to buy dual-tubed, binocular-style night vision goggles to give soldiers greater depth perception than offered by the current single-tubed Enhanced Night Vision Goggles and AN/PVS 14s.

The Enhanced Night Vision Goggle B uses a traditional infrared image intensifier similar to the PVS-14 along with a thermal camera. The system fuses the IR with the thermal capability into one display. The Army is considering equipping units trained in subterranean ops with ENVG Bs, the source said.

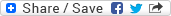

Units will also need special, hand-carried ballistic shields, at least two per squad, since tunnels provide little to no cover from enemy fire.

Weapon suppressors are useful to cut down on noise that’s significantly amplified in confined spaces, the manual states.

Some of the heavy equipment such as torches and large power saws needed for breaching are available in brigade engineer units, Hedrick said.

“We definitely did put some effort into trying to identify a list of normal equipment that may not work and what equipment that we might have to look at procuring,” Hedrick said.

Jason Dempsey, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for new American Security, was skeptical about the scale of the program.

Dempsey, a former Army infantry officer with two tours in Afghanistan and one in Iraq, told Military.com that such training “wasn’t relevant” to fights in Iraq and Afghanistan.

He questions spending such a large amount of money training and equipping so many of the Army’s combat brigades in a type of combat that they might never need.

“I can totally understand taking every brigade in Korea, Alaska, some of the Hawaii units — any units on tap for first response for something going on in Korea,” said Dempsey, who served in the combat units such as the 75th Ranger Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division and the 10th Mountain Division.

“Conceptually I don’t knock it. The only reason I would question it is if it comes with a giant bill and new buys of a bunch of specialized gear. … It’s a whole new business line for folks whose business tapered off after Afghanistan.”

— Matthew Cox can be reached at [email protected].